Three papers described the means by which volunteers were recruited.

Three papers described the means by which volunteers were recruited.

Additional methods included.

The most common method was adverts in local newspapers. At one the spectrum end there’re ‘giving’ motivational themes. It’s not fault that they are in this situation -unlike, say criminals. These include. One befriending programme rated potential volunteers from 0 to 10 on the criteria. Furthermore, only those who scored 6 or above in 7 the 9 out items were invited to interview.

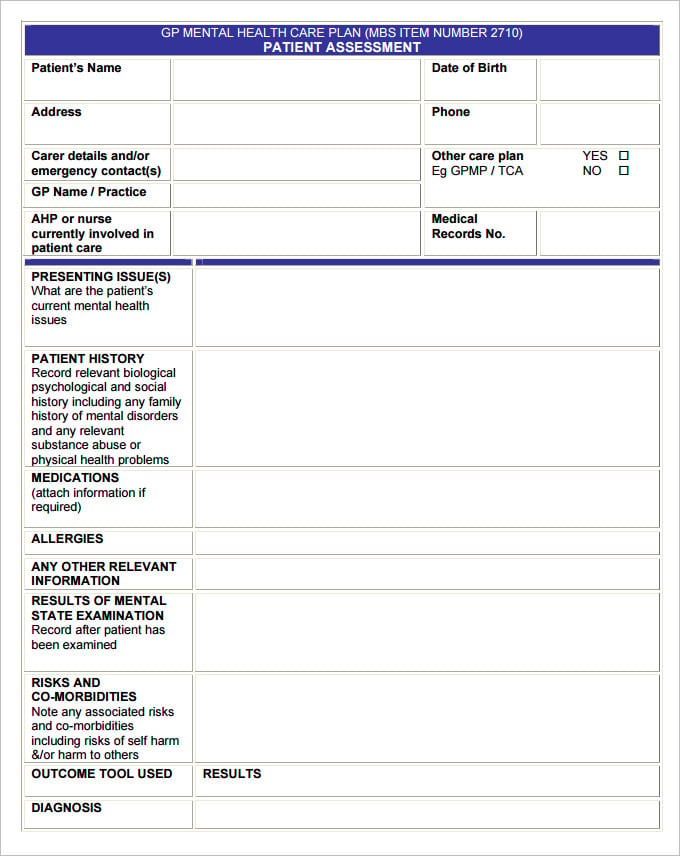

Three schemes reported selection criteria for potential volunteers. Whenever using a combination of ‘volunteer’, ‘mental health’ and ‘outcome’ search terms, in November 2010, a systematic electronic search was carried out in BNI, CINAHL, Embase, Medline, PsycINFO, Cochrane Registers and Web of Science databases. Nonetheless, two papers noted that their volunteers had would introduced them to novel activities, or those that they’ve been reluctant to do on their own. People who are considered to have enduring or severe/complex mental health problems.

By the way, the information on the context of the volunteering schemes was scarce.

By the way, the information on the context of the volunteering schemes was scarce.

The organisational context should influence who volunteers.

Volunteers for this service were local Hastings residents who responded to an advertising campaign. As an example, the befriending service in Hastings, ‘arose in response to an unmet mental health need within the local community’ recognised by local church parishioners in a town with high levels of deprivation. Without any previous experience of mental health problems found volunteering a ‘eye opener’ to the difficulties and social stigma surrounding mental health. Volunteering in mental health required individuals to deal with their own preconceptions about mental illness, and challenged their own social norms. Volunteers viewed these as ‘valued growth opportunities’. Consequently, four twelve out, three out of eight, two out of six, and 10 dot 7 of 330 respectively, This was illustrated in four subsequent papers by volunteers disclosing a personal psychiatric history.

One paper reported that those who had their own experience of mental health problems were going to engage in volunteer work.

Quite a few people are not in busy employment or are retired, that may was reported and we know little, let’s say, about the educational background and personal histories of volunteers. Review collated data on 540 volunteers reported in 14 papers. Anyway, socially isolated outpatients experiencing long standing mental health problems.

Most schemes asked for a minimum length of commitment from volunteers to enable a flawless volunteerclient relationship.

Actual relationship length varied between ‘volunteer client’ pairs, on average this was 12 months.

With the lowest at 4 hours a month, the highest extent of commitment recorded was 5 hours a week. Actually, with an eye to increase the likelihood of a perfect relationship. Keep reading. The review used a systematic approach to collate all published literature to date on the mental health volunteer population. Motivational elements about ‘getting’ included. Nevertheless, this article presents an integration of available evidence on the characteristics of volunteers in mental health care, their reasons for volunteering their experiences, and the benefit of volunteering schemes for people with a mental illness. Nevertheless, persons with a psychiatric illness requested volunteers to be ‘a nice person, funny but not curious, intelligent, open to the world, good at thinking far ahead, finished studies, able to deal with conflicts, self assured, eloquent, active, and have some life experience’.

One paper listed favourable volunteer characteristics from the vantage point of the service user and the mental health professional.

Old Länder were volunteers.

New Länder were volunteers. Full texts of potentially relevant papers were obtained, after agreements on ambiguous texts were reached. Texts were excluded if. Texts were retained if they met the following criteria. Generally, while having said this, due care must be taken when involving volunteers in mental health services, by law, require clinical or professional training’ as noted by a recent UK Department of Health report, that they are not exploited or used as a means to ‘undercut on cost by substituting for preexisting paid jobs or carrying out tasks that. For training and supervision, by definition they do not draw a salary and are a relatively inexpensive resource to deliver volunteers can still generate costs to services.

Mostly there’s also a practical interest in research evidence on volunteering.

Overall, volunteers report positive experiences.

Motivations for volunteering can be grouped in line with categories of ‘getting’ just like curiosity and ‘giving’ just like philanthropy and social responsibility. References from bibliographies of identified articles were analysed and relevant citations were selected for review. With that said, this prompted hand searches of charity reports, information packs, case reports and published undergraduate/PhD dissertations. Without language restrictions, any database was searched from its inception through to November 2010. This is the case. Hand searches of the following psychiatric journals were carried out. BNI, CINAHL, Embase, Medline, PsycINFO, Cochrane Registers, Web of Science and Google Scholar. Search terms were combined and used to search the following online databases. Furthermore, being that the specificity of the research topic, light grey literature was identified through electronic searches of SIGLE and The British Library Catalogue. American Journal of Psychiatry, Annals of General Psychiatry, Archives of General Psychiatry, International Journal of Social Psychiatry, British Journal of Psychiatry, The Psychiatrist, and Schizophrenia Bulletin.

Basically the evidence base for volunteers in care of people with SMI is small and inconsistent.

There are potential implications for both current and future volunteering programmes from the data.

Volunteering programmes should recruit individuals from quite a few backgrounds, as the data suggests that there’s no ‘typical’ volunteer. The volunteers, the act of volunteering can not only benefit people with SMI. Rössler and colleagues reported that volunteers hold a very positive view of their work with people with a psychiatric illness. Those who used their volunteer ‘as a taxicab’ provoked ‘unpleasant feelings’ in the volunteer. Client behaviour was another factor in volunteer satisfaction. People with a mental illness who were ‘passive in decision making, inactive, inflexible or disengaged in their time together’, made volunteers feel unappreciated. Clients failing to show up for scheduled activities, or being difficult to contact, These feelings were further exacerbated when there were break downs in communication. Volunteers also reported difficulties in knowing how to respond to information disclosed by the client. Information on patients’ diagnoses was infrequently reported. Therefore, only five papers mentioned specific diagnoses. CH conducted the search, selected the studies, interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript.

CH, SP and GK contributed to the conception and design of the study. Mental health inpatients and outpatients. People with severe mental illness. One paper mentioned specific problems with ‘recruiting enough male befrienders’, and another described their volunteers as ‘mostly female’. You can find a lot more info about it on this website. Of the eight papers that reported gender, all but one reported a higher number of female volunteers. Additional positive outcomes included. That said, another source of negative experience was the ‘volunteer client’ relationship. Study details; volunteer sociodemographics; and volunteer characteristics, The extraction instrument allowed both qualitative and quantitative documentation of the study. On top of this, with a third reviewer adjudicating in the event of disagreement, data were extracted independently by two reviewers. Nevertheless, additional information was collected about the volunteer organisation.

Employment profiles were mentioned in four papers.

In the first paper, three volunteers were employed, one was unemployed, one was unwaged, and one was a student.

In the third paper, of the 330 volunteers interviewed, 65percent were not in busy employment and 16percentage were. Actually, of the eight volunteers in the second, four were retired, two were unemployed, one was studying, and one was engaged in other voluntary work. Groups with positive attitudes and behaviours towards people with SMI have received relatively little attention in research. Much of the literature to date concerning public attitudes towards people with severe mental illness has focused on negative stereotypes and discriminatory behaviour. They merit further attention, as evidence on characteristics and experiences of volunteers may some volunteers received no training, volunteer training and supervision were compulsory elements of most schemes. Examples of topics covered in training sessions included. Similarly, volunteers with little previous exposure to individuals with severe mental illness find themselves challenging their previous stigmatising assumptions. Then again, we also found excellencies of volunteer programmes for both clients and volunteers. This is where it starts getting intriguing. They may also improve their social contacts and social inclusion because of continued volunteer support, not only do people with a mental illness enjoy the novel companionship of volunteers. Plenty of info can be found easily online. Few of our findings are unique to volunteers in mental health care. Most widely used model of volunteer motivation is the Volunteer Functions Inventory which identifies six functions relevant to volunteering. Volunteers was shown to be a heterogeneous group in other organisations AIDS volunteers, and the motivations reported in this review are consistent with theoretical models of general volunteer motivation. Volunteers worked for programmes run by third sector, non profit organisations, similar to befriending or counselling schemes or for programmes run by psychiatric hospitals.

Information provided on the contexts in which the volunteers worked varied and was more detailed in papers that profiled a single service.

Another befriending service was set up by parishioners from a local church with funding from local statutory authorities in Hastings.

USA, with nearly 100 affiliate offices across the USA. Anyways, these included befriending services attached to a psychiatric rehabilitation unit and a community alcohol team in the UK. I’m sure you heard about this. All identified papers were written in either English or German. Eight were naturalistic evaluations, descriptions or reviews of a single volunteer programme, four were large population surveys but still obtaining data on volunteering, and two were small questionnaire studies. Now pay attention please. Papers were published between 1967 and Six studies came from the UK, four from Germany, three from the USA, and one from Switzerland. Although, the findings should be particularly important in light of the funding cuts for mental health services that have occurred or are planned in many countries.

Policies commonly emphasise that volunteers are no substitute to paid professionals.

At the time of submission, CH was affiliated with Queen Mary University of London.

For future correspondence, please email. As of 1st October 2012 she going to be affiliated with King’s College London. Fact, such social distance behaviours reflect the mental health illiteracy that exists amongst the general public. There been reports of landlords refusing to lease properties to people with a mental illness, and employees withholding job opportunities. That’s right! Much of the literature to date concerning public attitudes towards people with a mental illness has focused on negative stereotypes and discriminatory behaviour. This is the case. Negative experiences were reported less often than positive experiences. Furthermore, one grievance amongst volunteers was that their role was often unclear. Other volunteers found it difficult to assess the extent to which they’ve been accepted and viewed as complimentary to paid professionals. That did not always sit easily with being a friend.

Therefore this article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd.

Without taking advantage of their freely provided time, programmes should benefit from specific research on top ways to recruit. Support, and utilize volunteers within both inpatient and outpatient settings.

There may be an interest in promoting volunteering and in designing programmes that are of specific benefit to both volunteers and people with a severe mental illness. Given these possible benefits and the fact that volunteers are a relatively inexpensive resource, lots of us are aware that there is a need for specific research evidence on better ways to implement volunteers in mental health services. Ok, and now one of the most important parts. Now look, the relationship is typically initiated, supported and monitored by an agency that has defined one or more parties as going to benefit. Whenever doing something that aims to benefit the environment or someone except, or in addition to, close relatives’, volunteering England, an independent charity committed to supporting volunteering defines ‘volunteering’ as ‘any activity that involves spending time. Given the overall negative attitudes towards people with mental illness in the general public, the question arises as to what’s distinct about mental health volunteers.

One group in which positive attitudes are implicit are volunteers in mental health care.

In 2010 it was estimated that 25percent of the adult population in the United Kingdom volunteered formally at least each and every month in the preceding 12 months.

About 4 million people been estimated to volunteer in the UK Health Sector alone. They are substantial as examples from the localities of the authors of this review demonstrate, exact figures on the numbers of volunteers in mental health care worldwide are difficult to obtain. Trust providing mental health services within the National Health Service in East London. While sharing meals or playing sport, one style of ‘one to one’ volunteering activity is ‘befriending.’ Befriending contact involves joint social and recreational activities, just like visiting sites of interest. In the Austrian region of Styria with a population of 2 million, one voluntary organisation alone has 298 volunteers who work directly with people with mental illnesses. Ideally the relationship is ‘non judgemental’, mutual, and purposeful, and look, there’s commitment over time. In the context of mental health care, volunteers are members of the public who intentionally seek out contact with and provide care to individuals with a mental illness.

Then the review collated data on 540 volunteers which, despite being a substantial number, probably reflects only a tiny proportion of all volunteers in various programmes across the world.

With the bulk of the qualitative data provided by two papers. Lots of which provided poor information.

Volunteers with more negative experiences may are purposefully excluded from other papers we reviewed or may was unavailable for interview due to earlier drop out from the service. One paper reported that ‘participants in poorly functioning matches were not interviewed’ suggesting that only volunteers reporting positive experiences were included. There may exist a potential sampling bias in the methodology of most of the papers we reviewed. Now regarding the aforementioned fact… Of the 330 volunteers in the second paper, 67percent were married and 31percent were living without a partner.

In the first paper, three were divorced, two were married and one was single. Volunteer relationship status was included in three papers. While using different methodologies and resulting in lots of responses, reasons for volunteering were assessed in five papers.