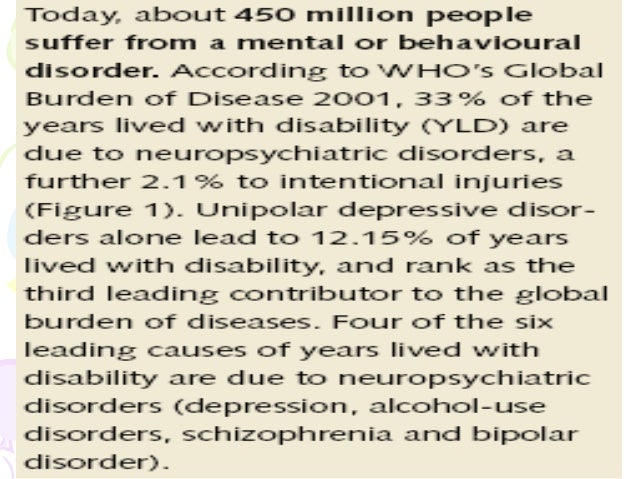

APTA will meet with CMS officials and Congress to address concerns about the challenges this process will present for bothproviders and patients. Surely it’s during this dance of invitation and acceptance that the first discussions of student mental health and campus services must happen. While eating disorders, ‘obsessive compulsive’ disorders, and substanceabuse histories, is well documented by professional organizations, researchers, and the popular media, the increase in the general amount of students coming to college already diagnosed with significant ‘mentalhealth’ challenges, including anxiety. While they are trying or pretending to listen to the police chief they are actually a great deal more interested in each other or their phones, the academic adviser, on which they are texting parents or friends back home. I know that the reality is that students probably absorb only about 25 the information percent shared by the parade of sessions and speakers. We do not talk about these problems in the year leading up to a student’s arrival on campus.

APTA will meet with CMS officials and Congress to address concerns about the challenges this process will present for bothproviders and patients. Surely it’s during this dance of invitation and acceptance that the first discussions of student mental health and campus services must happen. While eating disorders, ‘obsessive compulsive’ disorders, and substanceabuse histories, is well documented by professional organizations, researchers, and the popular media, the increase in the general amount of students coming to college already diagnosed with significant ‘mentalhealth’ challenges, including anxiety. While they are trying or pretending to listen to the police chief they are actually a great deal more interested in each other or their phones, the academic adviser, on which they are texting parents or friends back home. I know that the reality is that students probably absorb only about 25 the information percent shared by the parade of sessions and speakers. We do not talk about these problems in the year leading up to a student’s arrival on campus.

Whenever assuring them of the competence of our counselors, the availability of support, whatever it might take to keep them interested in us, we tend to provide the most generic information about services to students and families.

Whenever assuring them of the competence of our counselors, the availability of support, whatever it might take to keep them interested in us, we tend to provide the most generic information about services to students and families.

They just must ask.

In fairness to the very ethical and committed admissions professionals I’ve worked with over the years, families and students don’t share much themselves, afraid that they may lose this chance at admission to their dream institution. Should having heard in more detail during orientation about available services have made a difference? Essentially, what exactly should make a difference is for conversations about what a student truly needs and what a college can reasonably offer to happen as part of the admissions process.

I doubt it.

I doubt it.

Colleges must convince families that sharing such vital information wouldn’t lessen their student’s chance of admission, and it may well increase their student’s chance of success.

It’s only when the student arrives that the severity of their mentalhealth challenge becomes fully known to the campus, and even hereafter it may surface only when the student is in cr. Honest conversation between an admissions counselor and a prospective student and family, or between a counselingcenter director and an admitted student and family, will make more of a difference in that student’s chances of success than any orientation program ever could. Campus based group that supports students with mental illness, encourage these students to come out of the shadow of shame that ‘mental and’ ’emotionalhealth’ disorders can cast, And so it’s incumbent upon colleges to introduce their services as early as possible and begin a dialogue with families about whether such services might be enough, as advocates and organizations just like Active Minds.

I have two concerns with the orientation strategy.

One is that students in that setting do not absorb information quite the way we’re hoping they will.

We hope they will absorb it at a high enough level to make a difference when they need to recall it. I say that as someone who has planned, participated in, and evaluated orientation sessions on quite a few campuses. It began as early as the student’s first thoughts about applying, continued through emails, open houses, phone calls from alums, suddenly visits, and negotiations over ‘financial aid’ packages. Normally, in most cases, by the time a tally new student in cr is sitting in front of a dean of students who is trying a problem to untangle what’s going on, the student’s relationship with the institution is already a year old. I am sure that the bigger, more overwhelming issue is this. Although, the first day of a student’s orientation is so late to be discussing student mental health for the first time.