April 23, 2024

• Feature Story • 75th Anniversary

- Autism is a neurodevelopmental disorder that impacts how men and women interact, communicate, and study.

- Making early autism screening portion of routine well being care assists connect households to help and solutions as early as probable.

- Despite American Academy of Pediatrics suggestions, only a tiny fraction of pediatricians reported screening for autism at effectively-kid visits.

- NIMH-supported efforts to close the gap amongst science and practice have yielded essential insights into efficient tactics for expanding early autism screening.

- Researchers are identifying new tools for detection, new models for delivering solutions, and new tactics for embedding early autism screening and fast referral into routine well being care.

As quite a few parents of young young children know all also effectively, visits to the pediatrician generally involve answering a series of queries. Health care providers may well ask about the child’s consuming and sleeping habits or about their progress toward walking, speaking, and quite a few other developmental milestones. Increasingly, they’re also asking queries that could aid determine early indicators of autism.

Autism is a neurodevelopmental disorder that impacts how men and women interact, communicate, behave, and study. It is identified as a “spectrum” disorder since there is wide variation in the form and severity of symptoms men and women expertise.

Today, thanks to investigation focused on embedding routine screening in effectively-child checkups, the early indicators of autism can be identified in young children as young as 12–14 months. These efforts, quite a few supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), show that generating early autism screening portion of routine well being care can have a considerable effect on young children and households, assisting connect them to help and solutions as early as probable.

“This progress wasn’t inevitable or linear,” explains Lisa Gilotty, Ph.D., Chief of the Research Program on Autism Spectrum Disorders in the Division of Translational Research at NIMH. “Rather, it’s part of an evolving story that reflects the persistent, collective efforts of researchers and clinicians working to translate science into practice.”

Identifying the disconnect

The contemporary notion of autism as a neurodevelopmental disorder initial emerged in the 1940s and coalesced into a diagnostic label by the 1980s. Diagnostic criteria evolved more than time and, by the early 2000s, clinicians had proof-primarily based tools they could use to determine young children with autism as early as 36 months. At the identical time, proof recommended that parents may well notice indicators even earlier, in the child’s second year of life.

“Reducing this gap—between observable signs and later identification and diagnosis—became an urgent target for researchers in the field,” stated Dr. Gilotty. “The research clearly showed that kids who were identified early also had earlier access to supports and services, leading to better health and well-being over the long term.”

Researcher Diana Robins, Ph.D. , then a doctoral student, wondered regardless of whether an proof-primarily based early screening tool could possibly aid close the gap. With help from NIMH , Robins and colleagues created the Modified Autism Checklist for Toddlers (M-CHAT) , which they introduced in 2001. They aimed to offer pediatricians with a uncomplicated screening measure that could determine young children displaying indicators of autism as early as 24 months.

The science behind early screening continued to create and get momentum more than the subsequent couple of years. By the mid-2000s, researchers have been exploring the possibility of applying many developmental screening tools—such as the Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales, First Year Inventory, and Ages & Stages Questionnaires—to determine early indicators of autism.

The expanding physique of proof did not go unnoticed. In 2006, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) issued proof-primarily based suggestions recommending autism-particular screening for all young children at the 18-month take a look at. In a later update, they advised adding a different autism-particular screening at the 24-month take a look at, recognizing that some young children may well begin displaying indicators a bit later in improvement.

To the investigation neighborhood, these new suggestions signified a big step forward for science-primarily based practice. But this sense of progress was quickly dashed by reality.

When researchers really surveyed well being care providers, they discovered that pretty couple of knew about or followed the AAP suggestions. For instance, in a 2006 study , 82% of pediatricians reported screening for basic developmental delays, but only 8% reported screening for autism. Most of the pediatricians stated they weren’t familiar with autism-particular screening tools, and quite a few also cited a lack of time as a considerable barrier to screening.

The disconnect amongst science and practice prompted concern in the investigation neighborhood. A series of conversations in scientific meetings and workshops led to a crystallizing moment for the employees at NIMH.

“There was a period of several years in which researchers would go off and do unfunded work and then bring it back to these meetings and say, ‘This is what I’ve been working on,’” stated Dr. Gilotty. “It was an impetus for those of us at NIMH to say, ‘We’re going to do something about this.’”

Bridging the gap

Gilotty worked with colleagues Beverly Pringle, Ph.D., and Denise Juliano-Bult, M.S.W., who have been portion of NIMH’s Division of Services and Intervention Research (DSIR) at the time, to synthesize many file drawers’ worth of distinct measures, meeting notes, and investigation papers and distill them into an NIMH funding announcement.

The announcement, issued in 2013, focused on funding for autism solutions investigation in 3 important age groups: toddlers , transition-age youth , and adults . NIMH eventually funded 5 5-year investigation projects that particularly examined screening and solutions in toddlers. The projects focused on interventions that emphasized early screening and connected young children to additional evaluation and solutions inside the initial two years of life.

In 2014, Denise Pintello, Ph.D., M.S.W., assumed the part of Chief of the Child and Adolescent Research Program in DSIR. She directed the investigation portfolio that integrated these projects, which sparked an concept:

“It was such an exciting opportunity to connect these researchers because the projects were all funded together as a cluster,” she stated. “I thought, ‘Let’s encourage these exceptional researchers to work closely together.’”

At NIMH’s invitation, the researchers on the projects united to kind the ASD Pediatric, Early Detection, Engagement, and Services (ASD PEDS) Research Network. Although the ASD PEDS researchers have been applying distinct investigation approaches in a variety of settings, coming collectively as a network permitted them to share know-how and sources, analyze information across investigation web-sites, and publish their findings together . The researchers also worked collectively to determine techniques that their information could aid address noticeable gaps in the proof base.

Building on the proof

Together, the ASD PEDS research have screened additional than 109,000 young children, yielding important insights into the most efficient tactics for expanding early autism screening.

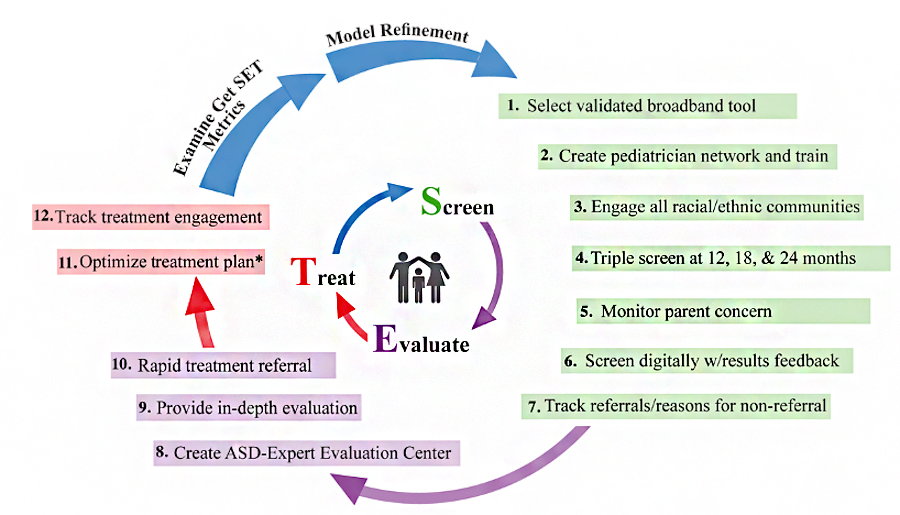

For instance, an ASD PEDS study led by Karen Pierce, Ph.D. , showed the effectiveness of integrating screening, evaluation, and therapy (SET) in an strategy referred to as the Get SET Early model.

Working with 203 pediatricians in San Diego County, California, Pierce and colleagues devised a standardized procedure that the providers could use to screen toddlers for autism at their 12-, 18-, and 24-month effectively-kid visits. The researchers also created a digital screening platform that scored the benefits automatically and gave clear suggestions for deciding when to refer a kid for additional evaluation.

These improvements boosted the price at which providers referred young children for further evaluation and sped up the transition from screening to evaluation and solutions. The study also showed that autism can be identified in young children as young as 12–14 months old, many years earlier than the nationwide typical of 4 years.

This and other research showed that incorporating universal early screening for autism into common well being care visits was not only feasible but efficient. Working closely with well being care providers permitted researchers to create trust with the providers and address their issues.

“There is this sense that if you sit down and really talk with pediatricians, you can bring them into the fold,” stated Dr. Gilotty. “Once you get some key people, you get a few more and a few more, and then it becomes something that ‘everybody’ is doing.”

Meeting the need to have

At the identical time, the ASD PEDS research have also explored techniques to attain households with young young children outdoors of major care settings. Numerous research have shown that some households are substantially much less most likely to have access to early screening and evaluation, such as non-English-speaking households, households with low household incomes, and households from particular racial and ethnic minority groups.

“Screening is most effective when everyone who needs it has access to it,” stated Dr. Pintello. “Addressing these disparities is a critical issue in the field and NIMH’s efforts have prioritized focusing on underserved families.”

One way to achieve this is to integrate standardized universal screening into systems that are currently serving these households. For instance, in a single study, ASD PEDS investigators Alice Carter, Ph.D. , and Radley Christopher Sheldrick, Ph.D. , worked with the Massachusetts Department of Public Health to implement an proof-primarily based screening process at 3 federally funded early intervention web-sites.

The researchers created a multi-portion screening and diagnosis procedure that integrated each clinicians and caregivers as essential selection-makers. They hypothesized that this standardized procedure would decrease procedural variations across the early intervention web-sites and aid to minimize current disparities in ASD screening and diagnosis.

The benefits recommended their hunch was appropriate. All 3 study web-sites showed an enhance in the price of autism diagnosis with the new process in location, compared with other intervention web-sites that served equivalent communities. Importantly, the standardized process seemed to address current disparities in screening and diagnosis. The enhanced price of diagnosis observed amongst Spanish-speaking households was additional than double the enhance observed amongst non-Spanish-speaking households.

Looking to the future

Researchers are continuing to discover the ideal techniques to place current proof-primarily based screening procedures into practice. At the identical time, NIMH is also focused on investigation that seeks to create new and enhanced screening tools. Evidence from neuroimaging and eye tracking research suggests that, despite the fact that the age at which observable attributes of autism emerge does differ, subtle indicators can be detected in the initial year of life. NIMH is supporting a suite of projects that aim to validate screening tools that can be made use of to determine indicators of autism prior to a child’s initial birthday.

“In other words, are there measures we can use to identify signs even before parents and clinicians begin to notice them?” explained Dr. Gilotty. “This is the critical question because the earlier kids are identified, the earlier they can be connected with support.”

These projects leverage sophisticated digital tools to detect subtle patterns in infant behavior. For instance, researchers are applying technologies to determine patterns in what infants appear at, the vocalizations they make, and how they move. They’re applying technologies to examine synchrony in infant–caregiver interactions. And they’re establishing digital screening tools that can be administered by way of telehealth platforms.

The hope is that new tools identified and validated in this initial stage will go on to be tested in massive-scale, genuine-planet contexts, reflecting a continuous pipeline of investigation that goes from science to practice.

“As a result of targeted research funded by NIMH over the last 10 years, we are seeing new tools for detection, new models for delivering services, and new strategies for embedding early screening and rapid referral into routine health care,” stated Dr. Pintello.

“I feel like it’s just the beginning of the story—we are just now seeing the impact of bringing science-based tools and practices into the hands of health care providers. Over the next few years, we hope that ongoing efforts to bridge science and practice will help us meet the unique needs of children at the exact time that they need services.”

Publications

Broder Fingert, S., Carter, A., Pierce, K., Stone, W. L., Wetherby, A., Scheldrick, C., Smith, C., Bacon, E., James, S. N., Ibañez, L., & Feinberg, E. (2019). Implementing systems-primarily based innovations to increase access to early screening, diagnosis, and therapy solutions for young children with autism spectrum disorder: An Autism Spectrum Disorder Pediatric, Early Detection, Engagement, and Services network study. Autism,23(3), 653–664. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361318766238

DosReis, S., Weiner, C., Johnson, L., & Newschaffer, C. (2006). Autism spectrum disorder screening and management practices amongst basic pediatric providers. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 27(2), S88–S94. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004703-200604002-00006

Eisenhower, A., Martinez Pedraza, F., Sheldrick, R. C., Frenette, E., Hoch, N., Brunt, S., & Carter, A. S. (2021). Multi-stage screening in early intervention: A important technique for enhancing ASD identification and addressing disparities. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51, 868–883. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04429-z

Feinberg, E., Augustyn, M., Broder-Fingert, S., Bennett, A., Weitzman, C., Kuhn, J., Hickey, E., Chu, A., Levinson, J., Sandler Eilenberg, J., Silverstein, M., Cabral, H. J., Patts, G., Diaz-Linhart, Y., Fernandez-Pastrana, I., Rosenberg, J., Miller, J. S., Guevara, J. P., Fenick, A. M., & Blum, N. J. (2021). Effect of household navigation on diagnostic ascertainment amongst young children at threat for autism: A randomized clinical trial from DBPNet. JAMA Pediatrics, 175(3), 243–250. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.5218

Pierce, K., Gazestani, V., Bacon, E., Courchesne, E., Cheng, A., Barnes, C. C., Nalabolu, S., Cha, D., Arias, S., Lopez, L., Pham, C., Gaines, K., Gyurjyan, G., Cook-Clark, T., & Karins, K. (2021). Get SET Early to determine and therapy refer autism spectrum disorder at 1 year and learn things that influence early diagnosis. The Journal of Pediatrics, 236, 179–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.04.041

Robins, D. L., Fein, D., Barton, M. L., & Green, J. A. (2001). The Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers: An initial study investigating the early detection of autism and pervasive developmental problems. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31, 131–144. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010738829569

Sheldrick, R. C., Carter, A. S., Eisenhower, A., Mackie, T. I., Cole, M. B., Hoch, N., Brunt, S., & Pedraza, F. M. (2022). Effectiveness of screening in early intervention settings to increase diagnosis of autism and minimize well being disparities. JAMA Pediatrics, 176(3), 262–269. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.5380