Whenever offering the opportunity to observeinteraction patterns in close relationships thatmay compromise health, similar evidence has emerged from laboratorystudies.

Whenever offering the opportunity to observeinteraction patterns in close relationships thatmay compromise health, similar evidence has emerged from laboratorystudies.

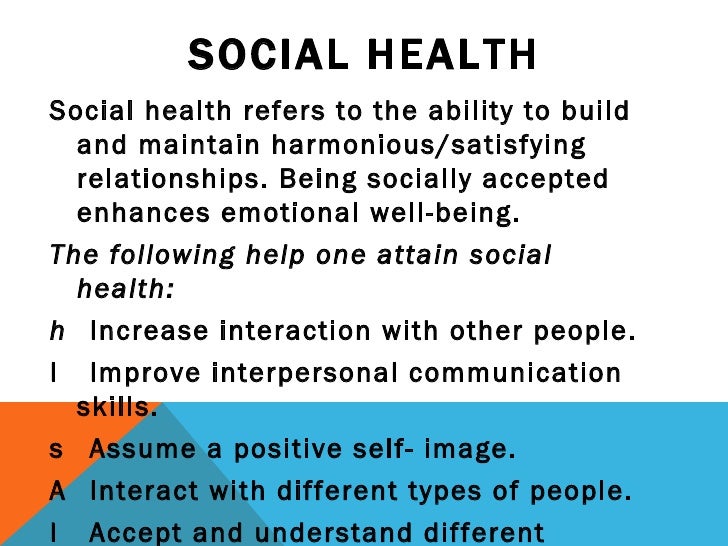

In a typical study,married couples are brought into a laboratoryand asked to discuss a current area of disagreementin the relationship.

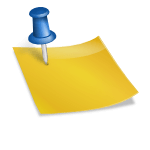

Negative and hostile behaviors duringsuch discussions are found to be associatedwith increased blood pressure, releaseof stress hormones, and declines in immunefunction. Researchers observe the spouses’ verbaland nonverbal behaviors, and record theirphysiology, as these discussionsunfold. Notice, also those thatarouse mixed feelings, Thus, it’s not only bad relationshipsthat may compromise health. Ambivalentsocial ties serve as sources of positive andnegative exchanges, and such ties havebeen found to be about poor healthrelatedoutcomes, including functionalimpairment, elevatedblood pressure, and shorter telomere length. Also, in taking stock of the evidence linkingnegative social exchanges to ‘healthdamagingphysiological’ processes and poor health outcomes,it is worth noting that these exchangescan occur in relationships that are ambivalentrather than exclusively problematic. Suchomissions can cause considerable distress.In one study, women who had experienced a significant stressful life event were most vulnerableto depression when the support they hadanticipated from a partner was not forthcoming.

Negativesocial exchanges also include being let down byothers when support was expected or beingexcluded by others from social activities.

Negativesocial exchanges also include being let down byothers when support was expected or beingexcluded by others from social activities.

Definitions generally referto behaviors by others that will beviewed as misdeeds or violations of relationshipnorms and experienced as unpleasant, unwanted,or insensitive, negative social exchanges was defined ina number of ways.

Examples include others’critical or insensitive comments, selfish actions,demands, intrusions, and interference. In one large study, middle aged Israelimen who reported more difficulties with theirspouses and children experienced an increasedrisk of death due to stroke over a ‘twentythreeyear’ period. In a large study of women in the UnitedStates, those who had previously been diagnosedwith breast cancer and who experiencedmore demanding and intrusive interactionswith their going to die over a ‘nineteen year’ period. Such increased understanding, inturn, might contribute to increased relationshipcloseness that benefits health. Consequently, another possibilityis that disagreements, I’d say in case not if such pressure fosters sustainedimprovements in health behaviors, itmight contribute to greater longevity eventhough Undoubtedly it’s experienced as aversive, One possible explanation for these counterintuitivefindings is that people may pressurechronically ill family members to improve theirhealth behaviors.

Now let me ask you something. How do negative social exchanges get underthe skin to damage health?

Now let me ask you something. How do negative social exchanges get underthe skin to damage health?

In one large study, ‘middleaged’ adults who reported more negative interaction exhibitedworse cortisol regulation.Notably, so this association was strongest amongparticipants who had experienced more frequentnegative interactions over a ten year period.

These hormones activate or deactivatebodily systems to prepare the body deal with the stressor. Whenthe stressors are prolonged or recurring, stresshormones remain elevated, that can damagebodily systems. Release of stress hormones slowsand ordinary bodily functions resume. Promisingclues come from studies of physiological processesassociated with negative social exchanges, the answer to thisquestion is still being investigated.

Social relationships can be a source of mixedblessings. On the one hand, close relationshipscan provide emotional support and instrumentalassistance that lifetime. Older adults who experienced morenegative social exchanges were more likely experience worsening disability and were alsoless going to experience disability remission. One study examined trajectoriesof disability being that some older adultsdecline rapidly, whereas others exhibit a relativelystable pattern of disability, and still othersmay experience improvements in functioningover time. For instance, existing research suggests theanswer is yes. Are they related more objective parts of health, like diseaseand disability, negative social exchanges are linked worse self rated health. For instance, the key question was whether negativesocial exchanges played a role in downwardtrajectories, and here, like surgery. Research in thisliterature typically includes controls for theinfluence of sociodemographic characteristics,comorbid health conditions, biological riskfactors, and health behaviors on participants’health status, and the longitudinal studiesroutinely control for baseline health.

Social relationships can be a source of mixedblessings. On the one hand, close relationshipscan provide emotional support and instrumentalassistance that lifetime. Older adults who experienced morenegative social exchanges were more likely experience worsening disability and were alsoless going to experience disability remission. One study examined trajectoriesof disability being that some older adultsdecline rapidly, whereas others exhibit a relativelystable pattern of disability, and still othersmay experience improvements in functioningover time. For instance, existing research suggests theanswer is yes. Are they related more objective parts of health, like diseaseand disability, negative social exchanges are linked worse self rated health. For instance, the key question was whether negativesocial exchanges played a role in downwardtrajectories, and here, like surgery. Research in thisliterature typically includes controls for theinfluence of sociodemographic characteristics,comorbid health conditions, biological riskfactors, and health behaviors on participants’health status, and the longitudinal studiesroutinely control for baseline health.

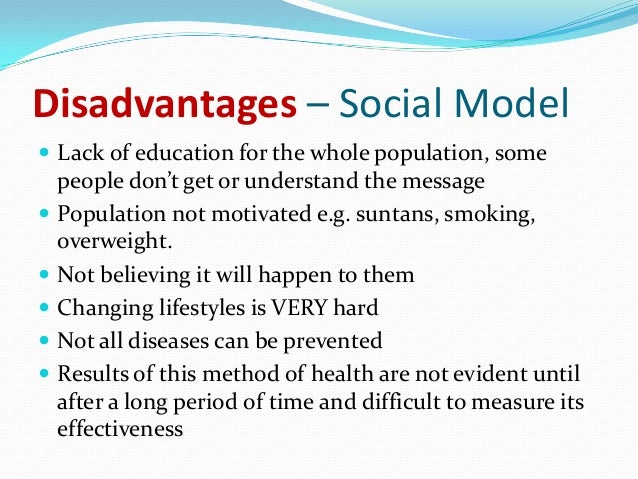

Epidemiologicaland survey studies generally have drawnupon large representative samples, and mostof these studies have used longitudinal designsthat allow for prospective analyses of health outcomesand transitions.

Althoughmore work needs to be done to resolve remaining uncertainties about causality, the strikingconvergence of findings across these differentstudies suggests that continued attention persistent negative social exchanges is warrantedin order to develop a comprehensive understandingof the role of with that said, this conclusion is supportedby evidence derived from carefully controlledstudies using diverse methods and samples andexamining multiple facets of health. They offer the advantagesof experimental control, observational assessmentsof negative behavior, and the opportunityto conduct physiological assessments ‘duringreal time’ social interaction, laboratory studies ofnegative interaction use smaller and less representativesamples. Rather than in peripheral relationships, negative exchangesoften take place in family relationships andfriendships, that helpsexplain their strong impact. Social relationships can also be a sourceof conflict, demands, and disappointments thatdetract from health and wellbeing.

That said, this article providesan overview of research on the associationbetween negative social exchanges and physicalhealth in later lifespan, and highlights implicationsfor future research and collaboration on interventionsdesigned to limit the healthrelatedtoll of negative social exchanges.

Such findings havestimulated research on the nature and effects ofnegative social exchanges.

Negativeexchanges with particularly important question thatemerges from this research and one of potentialsignificance to researchers and practitioners asks what makes some older adults morevulnerable than others to negative socialexchanges. Whenever andidentifying the factors that increase theirlikelihood of experiencing or being adverselyaffected by such interactions is an importantchallenge for any future research, studies of age differences suggestthat older adults generally are less likely thanyounger age groups to experience negativeinteractions with others, Undoubtedly it’s clear that can’t help feeling hurt that he does notseem to need to spend time with her. Notice that an olderman in declining health has noticed that hisdaughter has become critical and bossy aboutwhat he must do to prevent further healthproblems.

Recently she hasnoticed that he calls and stops by to visit lessfrequently, an older widowed woman appreciates themany ways her son helps her with importanttasks and decisions.

In spite the fact that older spouses generallyexhibit greater warmth and less hostility wardtheir partners during conflict discussions, these patterns are found in older andin middle aged couples.

In one latemiddle study aged married couples, marital discordwas already associated with asymptomatic coronaryartery disease. Thephysiological processes triggered by abrasivemarital conflicts could increase the risk ofchronic disease onset or progression if theconflicts recur frequently. So, among people who experience chronic orrecurring stressors over time, the repeateddemands on the body of responding to stress canlead to dysregulation across multiple physiologicalsystems. Intergenerational or culturaldifferences in expectations for support andcompanionship that kindle hurt feelings orresentments; impediments to the use ofavoidance as a strategy for limiting aversiveinteractions; personal characteristics that may contribute to relationship tensions; and the lingering effects of childhoodadversity that can impair social relationships inadulthood and increase physiological reactivityto conflicts, Evidence derived from large epidemiologicalstudies that create substantial needs for supportand overwhelm existing support providers.

Forging a greater understandingof how such factors operate in affecting vulnerabilityto persistent negative social exchanges iscrucial to building a strong scientific foundationfor designing interventions to strengthen socialties between older adults. That said, this accumulated wear and tear onmultiple bodily systems is referred to as allostaticload, andit underlies a broad range of chronic healthconditions. These studies controlled for participants’sociodemographic characteristics, cooccurringhealth conditions, and initial health status, andsome studies also controlled for biological riskfactors and health behaviors. Instead, it seems more likely thatexperiencing frequent or recurring negative exchangeswith members of one’s social networksets physiological processes in motion thatdamage health over time. Inclusion of such concontrolsmeans that the adverse effects of negativesocial exchanges are unlikely to be due lower income, poor health behaviors, or otherrisk factors.

Clues about theseprocesses come from research, discussed later,that has linked negative social exchanges physiological functioning.

In view of the evidence linking negative socialexchanges to poor physical and cognitive health,we might ask whether such exchanges are relatedto mortality.

Now this possibility is just beginningto be explored, and while are linked to an increasedrisk of suicidal thoughts and feelings.

One study distinguished between differentkinds of negative social exchanges to ascertainwhether a particular type was most strongly relatedto suicidal ideation. As well, other research has underscored the need to consider social exclusion for understanding how social relationships affect health and ‘well being’. Not lack of instrumental support or emotional support, was associated with greater suicidal ideation, it revealed that social exclusion.

Althoughgreater family conflict and loneliness predictedan increased risk of suicide among people ages75 and older in a Swedish study, whether negative social exchanges increasethe risk of suicide isn’t yet known.

Interventionsdesigned to similar to marital infidelity or elderabuse. Worriesabout family members’ orfriends’ difficulties may take atoll on physical or psychologicalhealth,but this article focuses on directly experiencedinterpersonal stress. It might be noted that strong effectson psychological health have also been documented, therefore this article emphasizes theeffects of negative social exchanges on physicalhealth. Actually the literature discussed also excludesanalyses of the health effects of exposure toothers’ interpersonal stress, like an adultchild’s contentious divorce ora friend’s loneliness. Now regarding the aforementioned fact… Rather than higher, puzzlingly, the latter study also revealed thatcriticism and demands from network memberswere associated with a lower,risk of mortality among chronically ill individuals.A similar counterintuitive finding emergedin another study in which greater negativity inparticipants’ relationships with their childrenand friends predicted a lower risk of mortalityover a ‘thirteen year’ period.

Sides of older adults’ health that have beenfound to be affected by negative social exchangesinclude self rated health, disease and disability,cognitive functioning, and mortality.

Key findingsthat have emerged from these lines of researchare discussed below.

As well as thosethat focus on older adults, studies that haveincluded middleaged adults are included in thediscussion below since a lot of the majorchronic conditions of later life begin or acceleratein middle adulthood. With that said, one could either foster positive interactionsin alternative relationships or facilitateother forms of stress reduction. Notice that they also mightwant to know whether problems that occurin particular kinds of social relationships orsettings pose unique challenges. That said, this goal most certainly could be achievedthrough collaboration between researchers andpractitioners, in which practitioners are ableto express their most pressing needs as theyconsider possible strategies and interventionsto benefit older adults with whom they work.Practitioners might seek for to know whether astrategy of helping older adults avoid or resolveproblems in key social relationships is more orless beneficial than a strategy of reducing ‘thehealthdamaging’ stress associated with suchproblems.